The

Chase - continued

Click all photographs for larger copies

Back at ground level, we were becoming simply overwhelmed with what this storm wanted to show us. As the sun began to filter into our location, we were on the south-westerly point of the main downdraft region. At around 1735 GMT we had a clear view of the massive shafts of hail hammering out of the westerly region of the downdraft, as clear skies began to show behind it to the north. Powerful CGs pierced down within 700-800m of our location, close enough for the shockwave to be distinguised from the soundwave. Two lightning bolts in particular, literally shook our insides as they nailed fields less than a kilometre away.

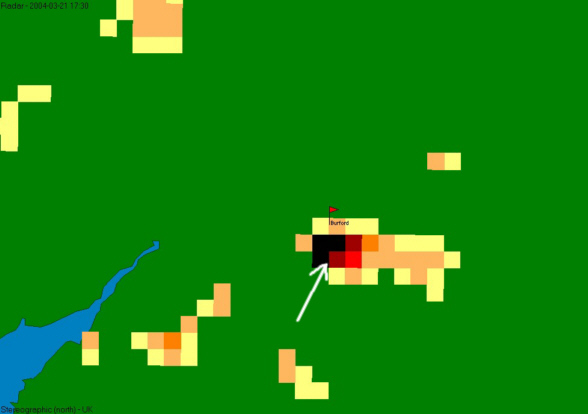

1730

GMT - A repeated image of the radar at 1730 GMT, although by 1735 our location

relative to the main downdraft (black) region was more on its western edge.

Looking

directly north, the rear (westerly) edge of the downdraft comes into view,

as vast shafts of torrential rain and hail are seen falling. The cloud base

at the top of this image rose vertically to form the back-sheared anvil, which

sprawled out directly over our heads.

By 1735 GMT, hail had almost stopped falling on our location, so we were under the impression that the downdraft's influence had left us. This was indeed the case, although we weren't prepared for the updraft to display to us one last spectacle. Directly above us at this point the only cloud left was the high, back-sheared anvil. However, in a mechanism common to the forward anvil, strong updrafts can throw large hail up into the anvil, dropping them sporadically vast distances away from the main downdraft. We believe this is a similar mechanism to that which next affected us, but with the hail thrown out into the back-sheared anvil instead. For a period of about two minutes, hail fell heavily from a seemingly precipitation-free sky. These stones were much larger than those which had already moved away; some reached between 20 and 25mm in diameter (nearly one inch, about the size of a 20 pence piece). The following images document this short but amazing fall of hail, launched from the updraft.

For

a brief period, as the large hail began to fall, the flanking line to our

south-west blocked out the sunlight allowing it to turn alarmingly dark. In

this image, the hail is seen falling despite the main downdraft being far

in the distant east.

As

the scene remained superbly dark, the large hail began to cover the small

lane that we had chosen as our vantage point.

This

image should leave no-one wondering why we were being battered and bruised

in our quest to capture the essence of the storm. Most of the stones in my

hand were greater than 10mm in diameter, with one or two over 20mm in size.

It

wasn't just us taking a beating from the large hail stones! Laura's car juddered

under the icy onslaught, although the coating seen here was achieved by surprisingly

few individual hailstones.

As

the sunlight returned, the hail slowly began to ease until only sporadic stones

fell with many

seconds between them. Such was the size of the hailstones, that what seems

at first glance like an accumulation on the road, can actually be traced to

each individual stone lying on the floor.

Despite

the plummeting temperatures and battering from icy marbles, we still managed

to muster a smile. In fact, we were both thrilled with what we'd just seen;

the only downside was that it was over and we had no way over keeping up with

the fast-moving storm!

The

final image of the storm as it moved away to our east shows perfectly the

large, rain-free updraft (to the right of the image (south)) and the intense

hail core of the downdraft (centre and left (east and north)).

As the cell moved eastwards, time was getting on, and by 1750 GMT the solar heating was almost non-existent. This lack of heating caused a sudden depletion in the storm cell, evident in the following radar images.

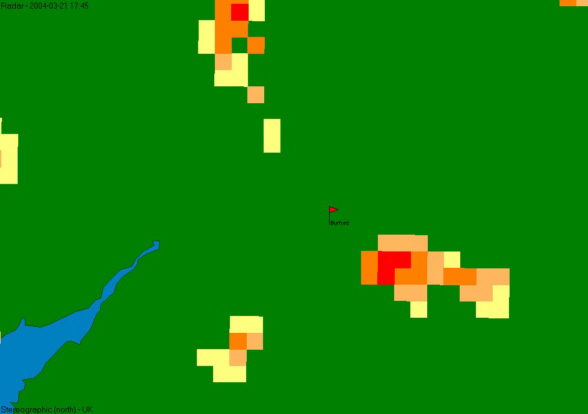

1745

GMT - The cell suddenly degrades, and although the downdraft core and anvil

precipitation are still evident, the maximum intensities fall to 3mm/hr (or

perhaps a sudden reduction in hail affected the radar return).

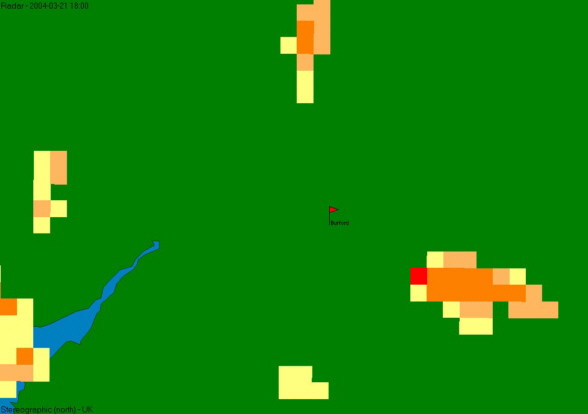

1800

GMT - The final radar image in this series shows the cell weakening yet further,

with a visible reduction in the size and intensity of the downdraft. However,

the cell continued as a comprehensive shower for a further hour, only fading

totally as it approached south London. If solar heating had continued, who

knows what havoc this storm could have unleashed.

Behind the storm, roads south of Burford were left coated in hail, up to an inch deep. The following images show the tricky journey back northwards to Burford - part of the reason we had no hope of keeping up with the storm.

Analysis on this storm follows...